Vax-Before-Travel Vaccines

Vax-Before-Travel Travel Vaccines 2024

Getting vaccinated against infectious diseases is one of the most effective ways to protect your health while traveling abroad, says the World Health Organization (WHO). Various U.S. Food and Drug (FDA), UK NHS, and European Medicines Agency (EMA) vaccines are approved for international travelers. The WHO published an updated List of vaccines in 2024. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most travel vaccines should be administered at least one month before departure to ensure maximum protection. The CDC lists the minimum ages and intervals between doses for available travel vaccines recommended in the U.S.

Travel Vaccine Advisories

The U.S. CDC publishes Travel Health Advisories and Travel Assessment, which enable travelers to confirm vaccine requirements for each country. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), U.K. Foreign Travel Advice, and the European Centers for Disease Control (ECDC) publish vaccine recommendations. Healthmap.org publishes disease outbreaks that are segmented by country. The U.S. Department of State publishes Travel Advisories, and U.S. embassies issue travel security notices. As of April 2024, the CDC has published guidance for cruise ships on acute respiratory illness management and prevention. The Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit provides actionable entomological intelligence that best assesses global vector-borne disease risks.

Travel Vaccination Appointments

Travel vaccine appointments are available at local clinics and pharmacies in 2024.

Anthrax Vaccines

CYFENDUS ™ (AV7909, BioThrax®), a two-dose anthrax vaccine for Post-Exposure Prophylaxis, was approved on July 20, 2023. In 2023, 1,166 suspected anthrax cases were recorded in Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Avian Influenza Vaccines

Audenz™ is a U.S. FDA-approved monovalent, adjuvanted, cell-based inactivated subunit vaccine. Avian influenza (bird flu) outbreaks continue in April 2024.

Chikungunya Vaccines

As of 2024, there is one approved chikungunya vaccine. IXCHIQ® (VLA1553) is an approved monovalent, single-dose, live-attenuated chikungunya vaccine. It is currently the only vaccine showing fully sustained titers one year after a single vaccination.

Cholera Vaccine

As of April 2024, cholera vaccines remain on allocation, with limited availability. Three WHO-prequalified two-dose oral cholera vaccines, Dukoral®, Shanchol™, and Euvichol®, are used for international travelers.

Vaxchora is an oral cholera vaccine for active immunization against disease caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1.

DUKORAL® is available in Europe, the U.K., and various countries.

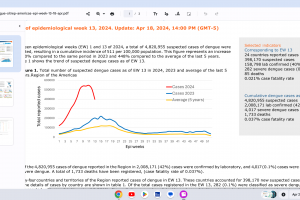

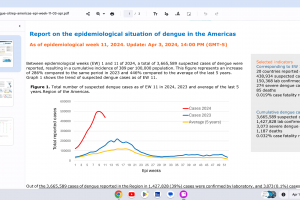

Dengue Vaccines

In April 2024, various countries have approved two dengue vaccines, and several candidates are conducting clinical trials.

Dengvaxia® is a live attenuated tetravalent chimeric vaccine licensed in the U.S. and elsewhere.

QDENGA® is a tetravalent dengue vaccine licensed in Indonesia, Europe, the U.K., and Brazil.

Diphtheria Vaccines

Diphtheria outbreaks continue in countries such as Guinea and Niger. In recent years, there have been outbreaks of diphtheria due to inadequate vaccine coverage, as about 16% of children are not fully vaccinated, says the WHO. The U.S. CDC says travelers two months and older traveling to outbreak areas should receive an age-appropriate dose of diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine if they are not fully vaccinated or have not received a booster dose within five years before departure. There are 11 vaccines available to help protect against diphtheria in 2024.

Ebola Vaccines

Zaire Ebolavirus vaccines have limited availability in 2024. Ebola outbreaks in Africa began in 1976 and continued in 2024.

Ervebo, Ebola Zaire Vaccine, Live, is a recombinant, replication-competent Ebola vaccine.

Combining Zabdeno (Ad26.ZEBOV) and Mvabea (MVA-BN-Filo) is an Ebola vaccine therapy.

Ebanga™ (mAb114, Ansuvimab-zykl) is a human monoclonal antibody approved for treating Zaire ebolavirus infections.

Sudan Ebolavirus vaccines are being developed in clinical trials.

Hajj and Umrah Vaccinations

The Saudi Ministry of Health established vaccine requirements for visitors to obtain an Entry Visa for Hajj and Umrah in 2024.

Influenza Vaccines

Flu shots are recommended for international travelers wherever influenza viruses spread.

Japanese Encephalitis Vaccines

JENVAC is a single-dose inactivated Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine. This Vero cell-derived vaccine is prepared from the virus's Indian strain (Kolar- 821564XYs).

Ixiaro is an inactivated, adsorbed Vero cell culture-derived vaccine targeted against the Japanese encephalitis virus. It is prepared by propagating JEV strain SA14-14-2 in Vero cells.

Lassa Fever Vaccine

Lassa fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic fever without an approved vaccine in 2024.

Lyme Disease Vaccines

Lyme disease vaccine candidates are conducting late-stage clinical studies. VLA15 is a multivalent recombinant protein vaccine candidate that protects people. Lyme disease outbreaks continue in Europe and the United States in 2024.

Malaria Vaccines

Malaria outbreaks continue in March 2024, and vaccines are available in Africa but not in the U.S.

Mosquirix (RTS,S/AS01e) is a recombinant vaccine that triggers the immune system to defend against the first stages of infections when the Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasite enters the human host's bloodstream through a mosquito bite.

R21/Matrix-M™ Malaria vaccine is produced by the Serum Institute of India and developed by scientists at the University of Oxford in England. As of October 2023, the WHO recommends it.

Marburg Disease Vaccines

Marburg vaccine candidates are conducting clinical trials, and various Marburg disease outbreaks have been reported in 2023.

Measles Vaccines

Measles outbreaks continue in April 2024, including in the U.S. Various measles vaccines are available.

M-M-R II vaccine is also known as the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Virus Vaccine Live, a live virus vaccine containing weakened forms of the measles, mumps, and rubella virus. M-M-R II works by helping the immune system protect itself from these viruses.

Priorix is currently licensed in over 100 countries. It is recommended for use in individuals aged ≥nine months, according to a 1- or 2-dose vaccination scenery.

MERS Vaccine

As of 2024, no approved MERS-CoV vaccines exist, but cases continue to be reported in the Middle East. The VTP-500 vaccine candidate completed Phase I clinical trials in Britain and Saudi Arabia, and the University of Oxford a Phase Ib trial in the U.K. to assess the vaccination of older adults.

Norovirus Vaccine

As of April 2024, the U.S. FDA has not approved a norovirus vaccine candidate.

Mpox Vaccine

The JYNNEOS smallpox-mpox vaccine is commercially available in certain cities reporting mpox outbreaks in April 2024

Nipah Virus Vaccines

Nipah virus vaccine candidates continue in phase 1 clinical trials in 2023. Since 1999, Nipah outbreaks have occurred in Asia, including Bangladesh and India.

Plague Vaccine

The WHO-Plague Vaccines in Preclinical Development and Clinical Trials was published in 2023. The primary outcomes were efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity, which were assessed using the Cochrane Collaborations tool. The study concluded that a single-dose F1-based mRNA-LNP vaccine protects the lethal plague bacterium.

Polio Vaccines

Polio vaccination, including booster shots, is recommended when visiting polio-endemic countries in 2024.

IPOL is a sterile suspension of three types of poliovirus: Type 1 (Mahoney), Type 2 (MEF-1), and Type 3 (Saukett). Sanofi Pasteur's single-antigen IPOL vaccine is a highly purified, inactivated poliovirus vaccine with enhanced potency.

Sabin Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine is a liquid trivalent vaccine produced from Sabin poliovirus type 1, 2, and 3 strains grown on Vero cells.

nOPV2 polio vaccine is derived from the live, infectious virus, but it has been 'triple-locked using genetic engineering to prevent it from becoming harmful. nOPV2 is genetically more stable than existing OPVs.

Rabies Vaccines

Various rabies vaccines and candidates seek to reduce rabies mortality in 2024.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

RMSF is endemic in multiple border states in northern Mexico, including but not exclusive to Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Nuevo León. As of December 2023, no approved RMSF vaccine exists. However, the CDC says early treatment with doxycycline saves lives.

Rotavirus Vaccines

Since 2019, four rotavirus vaccines have been prequalified by the WHO.

GSK's Rotarix is a live, attenuated rotavirus vaccine that exposes your child to a small dose of the virus, which causes the body to develop immunity to the disease.

Tick-Borne Encephalitis Vaccine

TicoVac vaccine is marketed by Pfizer Inc. under the brand names FSME-Immun® in Europe and TICOVAC™ in the U.S. It was developed using a master 'seed' virus similar to the tick-borne encephalitis virus found in nature.

Tuberculosis Vaccine

The BCG vaccine can prevent tuberculosis and tuberculosis meningitis and is used for nonspecific protective effects. Various BCG vaccines are available globally in 2024. T.B. outbreaks have been reported in certain U.S. states and multiple countries.

Typhoid Vaccine

Typhoid vaccines are available in 2023 and are recommended for people traveling to places where typhoid fever is common, such as South Asia (India).

Vivotif oral vaccine (capsules) is indicated for the immunization of adults and children over six years of age against disease caused by Salmonella Typhi. It contains live bacteria called Salmonella typhi strain Ty21a, which does not cause typhoid fever. Bavarian Nordic A/S owns Vivotif Oral and is available in the U.S.

Typbar TCV is a vaccine containing polysaccharide of Salmonella typhi Ty2 conjugated to Tetanus Toxoid.

Typhim VI is a sterile solution prepared from the purified polysaccharide capsule of Salmonella typhi (Ty 2 strain).

Urinary Track Infection Vaccine.

Uromune™ Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) inactivated, oral spray vaccine is approved in various countries. Recurring UTI vaccine appointment referrals are available at this PVax link.

Yellow Fever Vaccines

The WHO updated the country list containing yellow fever vaccine requirements.

YF-VAX® vaccine is licensed in the U.S. and requires about ten days to produce maximum immunity.

Stamaril® is distributed in over 70 countries in 2024, but not in the U.S.

Zika Virus Vaccines

While Zika virus outbreaks continue in 2024, the Region of the Americas reported 31,780 cases in 2023. No approved Zika vaccines are available in 2024.

Combination Travel Vaccines

Kinrix is a vaccine to prevent Diphtheria, Tetanus Toxoids, Pertussis, and Polio.

Pediarix is a vaccine containing noninfectious proteins from diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis bacteria, hepatitis B virus, and inactivated polioviruses.

Travel Vaccine Drug Interactions

Whenever a new medication is prescribed, the U.S. CDC says to check for known or possible drug interactions and inform the traveler of potential serious health risks. The CDC says during pretravel consultations, travel health providers must consider potential interactions between vaccines and medications. A study by S. Steinlauf et al. identified potential drug-drug interactions with travel-related medicines in 45% of travelers taking medications for chronic diseases.

Travel Vaccination Services

Travel vaccine hotspots in 2024 include Brazil, Cancun, Costa Rica, Florida, Haiti, Jamaica, New York, and Puerto Rico. In Texas, pre-departure travel vaccination services are offered in Austin, Cedar Park, Dallas, Houston, Lubbock, San Antonio, San Marcus, and Tyler. And in Massachusetts at Destination Health Travel Clinic.

US CDC Cruis Ship and Airport Alerts

The U.S. CDC Vessel Sanitation Program (VSP) requires cruise ships to report the number of people who say they have symptoms of gastrointestinal illness. The U.S. CDC's Traveler-based Genomic Surveillance (TGS) is a nasal sampling program testing people for Flu A/B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2, and other respiratory pathogens at leading airports in the U.S. TGS offers an early warning system to detect emerging infectious threats in near real-time. As of March 12, 2024, the CDC's Traveler-based Genomic Surveillance was conducted: Nasal swab only: Los Angeles, Miami, Newark, Seattle; triturator only: Boston; nasal swab + triturator: San Francisco; nasal swab + wastewater: NYC (JFK), Washington, DC (IAD); nasal swab at Chicago (ORD).

Travel Vaccine Certificates

The WHO and European Commission announced in 2023 that the European Union digital certification system will become a global system facilitating international mobility. In May 2023, a notice of End to Requirement was issued for air passengers to provide proof of vaccination before visiting the U.S.

Travel Vaccine FAQs

Frequently asked questions and answers related to travel vaccines are published by trusted sources, such as:

- Immunization Action Coalition

- The U.S. Health & Human Services

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- U.S. Department of State

- World Health Organization

- U.K. National Health Service

Note: This content is aggregated from various news sources and vaccine research organizations and has been fact-checked by healthcare providers, such as Dr. Robert Carlson.